2.0 What is proceduralization?

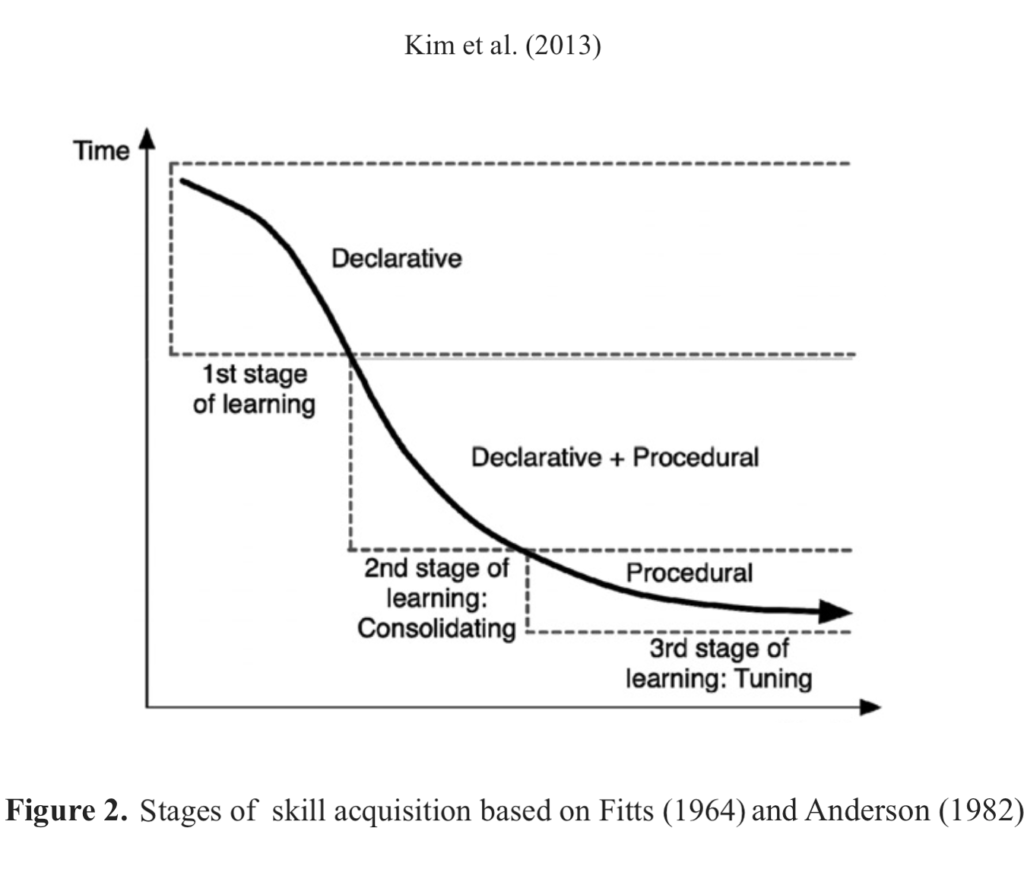

Many accounts of skill acquisition involve the concept of proceduralization — where declarative task-knowledge is practiced and replaced by procedural representations to become faster, more automatic, and less error-prone (Fitts, 1964; Anderson, 1982; Dreyfus, 1986; Kim, Ritter, & Koubek, 2013). This notion has been greatly useful in explaining the acquisition of physical skills in sports (Beilock et al., 2001; Ford et al., 2005) and cognitive skills such as mathematics (Anderson, 1993; Taatgen, 2013).

Stages

Skill acquisition has been described in psychology and philosophy as a progression from initial rule-following to an expert stage where several aspects of performance become more automatic, fast, and accurate (Fitts & Posner, 1967; Dreyfus & Dreyfus, 1986).

Explanations of skill are not exhausted by automaticity and cognitive control, and include factors such as flexibility and metacontrol (Pacherie & Mylopoulos, 2020) however they play an important role even at elite levels of skilled performance. One of the first models of skill acquisition was proposed by Anderson (1982) based on Fitts’s (1964) three stage theory. The first stage involves the initial learning of declarative task knowledge (e.g., instructions for tennis or driving). As task knowledge is acted out it begins to trigger production rules that carry out the performance. In the second stage, as task knowledge is repeatedly acted out it builds up production rules within procedural memory. With practice, performance speeds up and errors go down. In the third stage, actions are largely automatic and performed by productions that are further refined. In their meta-analysis, Newell and Rosenbloom (1993) reported that the increase in response time during practice demonstrated a power function of the number of practice trials. This they called “the Power Law of Practice”. The mechanism of skill learning in ACT-R is that of compilation, which is twofold process consisting of proceduralization and composition. During proceduralization, as task knowledge is replaced by production rules, the inefficient knowledge retrieval can be skipped. As a result, performance time speeds up and working memory load goes down. Composition is the process by which long chains of productions are merged and shortened. Expert performance is subject to further refinement mechanisms such as reward and time delayed learning where faster productions are rewarded.

Proceduralized skills and epistemic feelings

As declarative knowledge becomes proceduralized, the mechanisms of performance become less consciously accessible. This is the consequence of of procedural memory being cognitively impenetrable (Squire & Zola, 1996). As declarative knoweldge is replaced by procedural knowledge, the mechanisms of skill disappear below the horizon of conscious awareness. The result is that experts develop “a disconnection between what is done and what is accessible to self-report” (Beilock and Carr, 2001).

Since procedural memory is cognitive impenetrable, it employs another means of information to interact with higher executive functions. Research indicates that procedural knowledge uses epistemic (noetic) feelings to communicate with the central executive. Noetic data transmits an aggregate of information concerning a practiced skill. Noetic feelings have been shown to be a reliable indicator of the efficacy of one’s skill level (Hart, 1965; Rhodes & Castel, 2008). It has been shown that executive functions are routinely guided by noetic feelings of “rightness,” “wrongness,” and “certainty” (Mangan, 2001). Noetic feelings are considered a form of “meta-data” that communicates to the central executive one’s level of skill (West & Conway-Smith, 2019).

A common example of proceduralization can be observed in learning to drive a vehicle. Driving lessons begin with an instructor providing knowledge of how to use the keys, shift stick, gas pedal, etc. Initially, the novice driver’s movement are slow, clumsy, and error-prone. Over time the knowledge becomes builds up procedural knowledge that is fast and more accurate. Eventually, the procedural knowledge replaces the declarative knowledge entirely. Expert may even have difficulty communicating how to drive to a novice driver, as declarative knowledge has become obsolete. To an expert driver, proceduralized skills communicate by way of epistemic feelings such as the “noetic feeling of rightness” (Thompson et al. 2011). Other feelings such as the “rightness” and “wrongness” of actions guide an expert driver’s movements. This is one example of how as noetic feelings serve as an informational bridge between proceduralized skills and executive functions.

The previous example has illustrated how object-level skills become proceduralized. The following section, Section 3, will discuss how this process may also apply to meta-level skills. This subject will be modeled within the computational cognitive architecture ACT-R.